Only a few original testimonies remind us of what happened in the area of the settlement at the eastern outskirts of Hersbruck more than 75 years ago. In the search for suitable sites for underground armaments production facilities, the "Houbirg" located near Happurg came into the focus of the Reich War Ministry in the third year of the war. Geological investigations revealed that a sandstone layer (called Dogger) would be particularly suitable for the rapid construction of an underground production facility for BMW aircraft engines. For the construction of the tunnels, a suitable site for a concentration camp satellite camp was sought in the immediate vicinity.

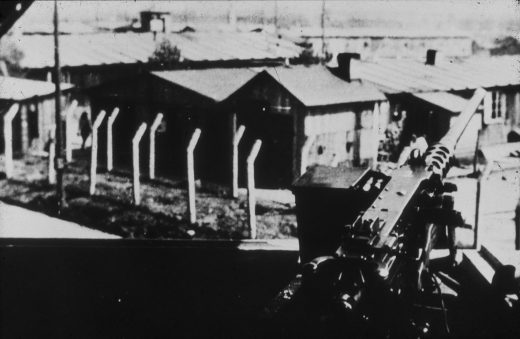

The choice fell on an abandoned Reich Labor Service barracks, which in the spring of 1944 was converted into the commandant's office of the SS Guards. On the surrounding Pegnitz meadows, the expansion of the site into the largest subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp began. In April 1944, the first prisoners arrived in Hersbruck and construction work began at full speed on and in the Houbirg under the camouflage name "Doggerwerk". In the months that followed, nearly 10,000 prisoners from over 23 nations were involved in the construction of the tunnels. The project was not completed until the end of the war, and production of aircraft engines never took place in the Houbirg.

After the Americans occupied Hersbruck in April 1945, the grounds of the concentration camp continued to be used temporarily as a prisoner-of-war camp for German soldiers. According to hearsay, one of the most famous inmates was Panzer General Heinz Guderian. Soon after, the area was used as an internment camp for former functionaries of the NSDAP. After the dissolution, the still standing barracks were occupied by so-called "displaced persons".

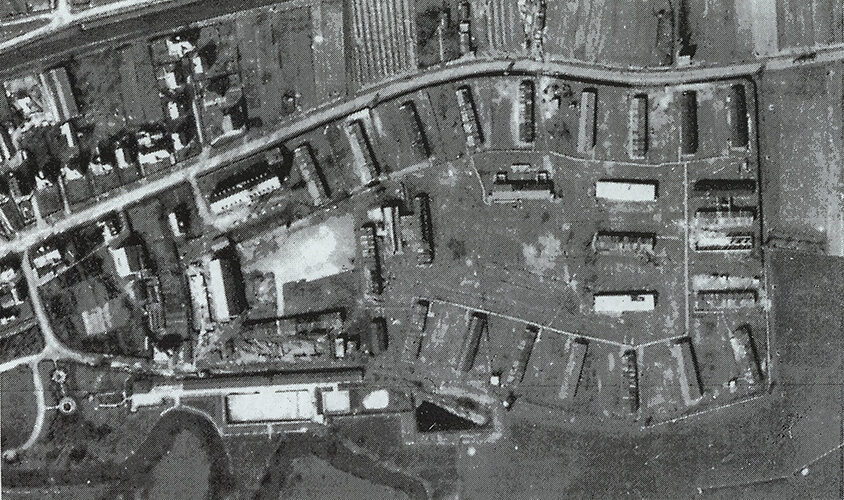

The remaining buildings were demolished in 1951 and a housing estate and a sports field were built. Only the former Reich Labor Service barracks (and later SS commandant's office) remained and only in 2007 had to make way for the new tax office, the "beauty" of which is certainly debatable. All in all, there are virtually no visible structural elements of the former camp grounds today. It is therefore all the more surprising that the authorities are apparently not interested in scientifically monitoring possible construction measures.

The former tennis court had to make way for a large construction project in the fall of 2022 and was gradually removed. If one compares old aerial photographs, one soon recognizes that a part of the roll call area and the camp kitchen was located on the area of the tennis court at that time. Furthermore, aerial photographs prove that apart from the construction of the tennis court, no construction has taken place on the area since the 1950s. One does not have to have studied history to come to the conclusion that a construction measure on such an area would most likely bring to light corresponding finds. Unfortunately, the state failed to order a corresponding investigation.

Several times I could observe the progress of the demolition work in passing. In December 2022, this work was finally completed and the site was cleared and freely accessible (there was no fence and no sign prohibiting access). Out of interest to see if any structural foundations of the storage buildings had been uncovered, I visited the area. And indeed: There were a lot of artifacts lying around on the surface. In addition to red bricks, which presumably served as the foundation of the kitchen building, remains of the sewage system of the time were visible, as well as numerous shards of the porcelain tableware of the SS guards (some plate shards were marked with "SS-Reich"). Among the gravel and mud, however, smaller relics were also found, such as buttons, e.g., the button of a German naval uniform. Probably the most revealing find was not recognizable to me as such at first. A small triangular aluminum plate caught my eye by its mere shape. I pocketed it and cleaned it at home.

Remnants of red paint were visible, as well as small mounting holes and the stamped number 52246. Although it became clear to me that this is probably some kind of identification badge, but I could not assign it in time. Similar tags are also used in livestock as ear tags. Only by an Internet search it became apparent that this was obviously the mark of a concentration camp prisoner. In an older newspaper article, a contemporary witness showed a stamp of the same design to the camera.

After this realization I immediately reported the find to the responsible monument office, whose employees were also very interested in the matter and accepted the find report. Furthermore, I contacted the local concentration camp memorial association, where they were also pleased about the find. An employee of the Flossenbürg concentration camp memorial finally helped me to find out the identity of the prisoner.

Quoting from the information: "The number was worn by a Russian prisoner who was transferred to Dachau in September 1943 and was transferred from the Dachau subcamp Allach to Hersbruck on August 25, 1944. During the transfer - as is very often the case with Eastern European prisoners - the personal data was transferred incorrectly. Thus, on paper there are now two prisoners, one from Dachau and one from Flossenbürger, but they are one and the same person. We will correct the data accordingly."

Dachau Andre Swiridenko (14.06.1916 Nebrat)

Flossenbürg Andrej Swindeko (14.09.1916)

Nebrat is a small village near Kiev, so the prisoner must have been Ukrainian. My guess is that he either came to a concentration camp as a soldier of the Red Army and thus later as a prisoner of war, or he was imprisoned for partisan activities and brought to Germany as a political prisoner. It was not possible for me to determine whether he survived his stay in Hersbruck. Did he lose the badge? Thrown it away at the end of the war? Or did he die and the badge was still on his clothes?

I would like to hand over the stamp to possible still living relatives - after consultation with the responsible monument office. Unfortunately, due to the current situation in Ukraine, it is difficult to conduct such research. I would be pleased about help and hints from the readership.

Adrian Matthes, Erlangen, März 2023

Prisoner number "52246

Sehr gut!!! und??? gibt es schon etwas neues?????

Aktuell laufen auf der Baustelle Ausgrabungen. Hier findet sich ein Zeitungsartikel dazu:

https://n-land.de/top-story/eine-spurensuche-an-einer-sensiblen-stelle

Nachtrag folgt!