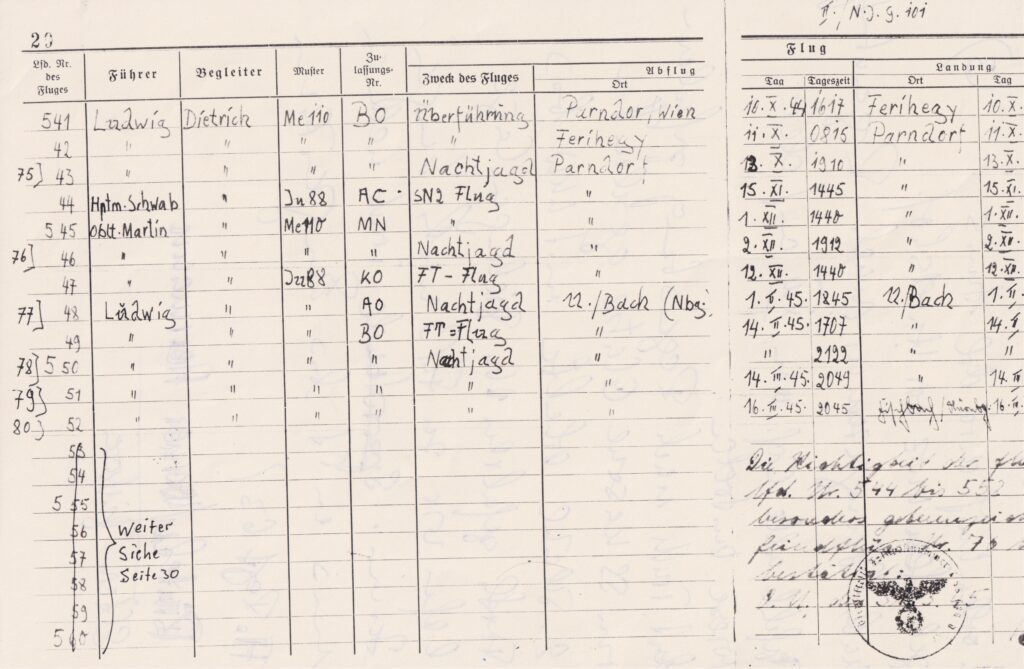

Pilot Leutnant Ludwig flew almost all types of night fighter aircraft, including the Me 110 and the Do 217/N. Together with on-board radio operator Anton Dietrich, he was credited with 13 aerial victories, mainly against British bombers. Ludwig achieved his last two victories in the night of March 16, 1945 in the airspace over Nuremberg during a major British raid. However, he was shot down himself.

The crew, Lt. Ludwig, was able to save himself by parachuting over Fischbach near Nuremberg. The Ju 88 G-series carried the registration 9W+BO and belonged to the 6th squadron of the II. group of Nachtjagdgeschwader 101, which was stationed in Unterschlauersbach west of Zirndorf. The crew included Lieutenant Herbert Ludwig (pilot), Sergeant Anton Dietrich (radio operator), NCO Erich Gränitz (mechanic) and Sergeant Major Rottmann (radio operator).

The Lancaster PA234 (crashed near Bürglein-Wendsdorf) and the Lancaster RF145, which presumably came down near Stalag 13d Langwasser, were among the confirmed kills of the Ludwig crew on the night of March 16-17, 1945. Lieutenant Herbert Ludwig described the events of March 16 in a letter to his wife Gertrud on March 21, 1945:

"During the last terrorist attack on Nuremberg, I shot down two four-engine planes in five minutes. I was in the middle of a group and saw 4 four-engine planes at once. I shot down two of them and was then shot down by a Mosquito. My ship was on fire and crashed. Your sweetheart was thrown back and forth in the plane and didn't get out. Then at least I had my upper body out of the shot-up canopy, but I was hanging helplessly in the plane, which was constantly turning and overturning, saw the ground approaching quite quickly and knew that it was coming to an end. I worked like a wild man and suddenly I was free, hurtling through the air, calmly pulling my parachute. It came out from between my legs, there was a little jolt and I was happy. I felt blood running down my face with satisfaction and I was floating. In between, I heard the roar of the flak and looked around. I was right above the Nazi Party Rally Grounds. I was shot down at 5,000 meters and had crashed over 3,000 meters with the burning plane. I don't know how I got to the ground. I only regained consciousness when soldiers carried me on a stretcher. I felt very sick, I had to get up and vomit. Then I found out that I had hit my head on an iron trolley when I landed. Then I fell unconscious. I suffered a concussion. I got a thick bandage around my head and went to sleep. The next day, I discovered that I was quite well. My eyelashes, eyelids and the hair at the back of my head were down. I only had minor scratches and bruises. Toni and Erich had already been ejected from the plane at 4500 meters. Our radio operator Ofw Rottmann also got out safely, but broke an ankle on landing. Toni is all right except for a burn on his head. Erich has something wrong with his breathing. That's why he went to the military hospital today. So the whole thing went well for us. There were 2 mosquitoes behind me on the penultimate mission. I shook them off, of course. However, I didn't expect them in Nuremberg. Rasper shot down a four-engine plane the same night and was also shot down by the rear gunner. I'll be flying again in 14 days at the latest. Every bomber that appears in my sights will stop dropping bombs on women and children. I will keep this word"

(Archive Friedrich Braun, letter from the estate of Herbert Ludwig to Mrs. Gertrud Ludwig)

The account that Herbert Ludwig was shot down by a Mosquito is to be doubted. The Mosquito had no oblique armament, and no Mosquito had claimed to have been shot down in the attack on March 16, 1945. Ludwig was therefore definitely shot down by one of his own night fighters. In the euphoria of the second successful kill, the radio operator to the rear must not have been paying attention.

The on-board radio operator Anton Dietrich volunteered for the Luftwaffe at the age of 17. On October 5, 1939, he donned the blue-grey uniform. After lengthy training at various radio schools, Dietrich was assigned to NJG 101 in April 1941 as an on-board radio operator. By April 23, 1945, he had a total of 567 flights to his credit, 95 of which were enemy flights. Anton Dietrich was awarded the EK I and the silver Frontflugspange for his successful launches and missions. He survived the war and described the events of March 16, 1945 to Friedrich Braun as follows:

"On the evening of the 16th, the order was once again to be on standby. Strong British bomber units flew over France towards southern Germany. As the units continued on their eastward course, we were cleared for take-off at 8.45 pm. Six Ju 88-G aircraft from the 6th Squadron of the II/NJG 101 were deployed on the bomber stream. On the fighter control frequency we were guided towards the fighters approaching from the west. The fighter leader led us directly into the bomber stream that night. When the jagged edges of the bombers appeared on my NS2 device, we recognized the shadows of four English bombers shortly afterwards. Herbert pushed the "Ju" under the closest flying aircraft. It was a four-engined Lancaster. We got into firing position at 9.35 pm. When Herbert had the bomber fully in the Fu.MG 202, he pressed the release button of the oblique armament (oblique music), the two MG 151/20 mm thundered off. After short bursts of fire, which disappeared directly into the fuselage of the enemy, the bomber took effect. The Lancaster smeared across the wing and tipped downwards, burning. While I was still watching the impact and noting the time, Herbert had already worked his way up to the next Lancaster. At 9.41 p.m. we were in firing position again. After a few hits from the oblique music, the bomber dismounted and hit the ground burning at Fischbach/Langwasser. We were fully engaged with this enemy at this stage and I still don't know how it happened. Suddenly there was a crash behind me in our plane. Moments later, I was literally torn out of my seat and plummeted down through the night. A Mosquito had probably sawn off the fuselage directly behind the cockpit with a sheaf. I was able to pull my ripcord. The canopy opened and I floated through the icy, ferrous air. The flak shells burst above me. When I heard the bl-bl-bl-bl-bl-bl of the bomber engines, I was terrified. I just thought, I hope I don't get caught on a wing or one flies straight into me. Lightning flashed and crackled below me over the city of Nuremberg. I drifted a little. As I approached the ground, I concentrated on landing. At the last moment, I skimmed past a church tower and immediately afterwards hit a relatively steep tiled roof. The parachute lay on the other side of the roof. I was hanging in the harness a few meters above the ground. The farmer must have heard the noise I made on the roof, because a short time later he arrived armed with a pitchfork. According to the local population, every parachutist had to be English. I explained the situation to the man in the purest Bavarian and asked him to get me out of my predicament. In the meantime, other civilians had joined us. They didn't quite trust me because I was wearing an English pilot's jacket that we had swapped from our comrades in the other field post number. Incidentally, my comrades did the same with the jackets. It was customary for the downed pilots to be brought to us at the airfield. They were entertained there. After the British or Americans no longer had any direct use for fur-lined leather jackets in captivity, we used this opportunity to trade them in. I had come down in Fischbach near Nuremberg. The people accompanied me to the mayor's office. From the police station, I was then able to contact my squadron in Unterschlauersbach. My comrade NCO Erich Gränitz, the on-board mechanic, landed in an anti-aircraft position near Fischbach. Erich would have preferred to stay there because, according to him, the position was full of pretty girls who were serving there as staff assistants or RAD maids. He was well looked after by the girls. That night we had a guest pilot, Ofw. Rottmann, on board with us. The people from the control center or other services were keen to complete a front flight with good crews, which was then noted in the performance book, possibly even as a launch participation. The Ofw. made the jump with a broken ankle. Only Herbert Ludwig, who initially couldn't get out of the plane, actually had greater difficulties."

(Archiv Friedrich Braun, Interview mit Anton Dietrich)

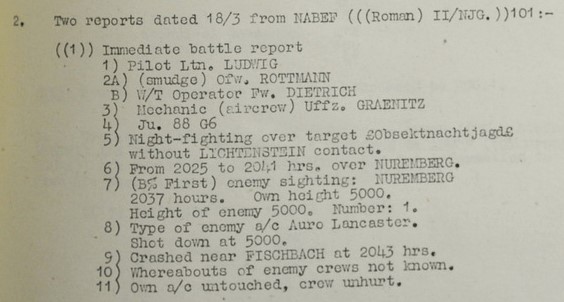

As described by Leutnant Ludwig, not only his aircraft crashed on the night of March 16-17, but also that of his comrade Leutnant Rasper. Further losses of NJG 101 that night are not known. The fate of the two crews, their deployment and the combat reports are well documented today, and not only through testimonies and letters. Radio messages intercepted by the British provide a detailed insight into the numbers and dates of the aircraft used that night. Unbeknownst to the Germans, the British intelligence service had cracked the German radio encryption system and was able to listen in on all radio messages, some of which were crucial to the war effort. The reports from II/NJG 101 about the mission on the night of March 16, 1945 were also meticulously recorded and thus documented for posterity. The second firing of the Ludwig crew, for example, was recorded on March 18, two days after the mission, as follows and sent to another office in encrypted form: (Note: the times were given in the British time zone, i.e. shifted by one hour)

The sequence of events is thus recorded in great detail. The only question that remains is where Lieutenant Ludwig's plane landed. It is said that one Ju 88 landed near Fischbach and one directly on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds near the Congress Hall that night. It is difficult to distinguish which of these aircraft was flying Ludwig and which Rasper, and it is not possible to make a clear distinction. On-board radio operator Dietrich describes that he landed directly in Fischbach, on-board mechanic Gränitz in the anti-aircraft position southwest of Fischbach and Ludwig himself states that he jumped directly over the Reichsparteitagsgelände. It is therefore obvious that the plane crashed roughly from east (Fischbach) to west (Reichsparteitagsgelände) and that the Ju 88 at the Congress Hall was Ludwig's plane. Braun must also have come to this conclusion, because in his documents he only states "Reichsparteitagsgelände" as the crash site of Leutnant Ludwig's plane. Presumably, Rasper's and Ludwig's aircraft crashed almost simultaneously in opposite directions in the airspace over Fischbach/Nuremberg. It is unlikely that there were any other eyewitnesses to the incident during the night bombing raid. There is also no information about the clearing of the debris. It is likely that the aircraft parts were hardly noticed later in addition to the large mass of debris.

But that was not the end of the Ludwig occupation chapter in the district: US vehicle convoys on the A 9 Berlin/Munich highway were the target of German jabos and night bombers several times near Lauf from April 16 to 25, 1945. Aircraft from the IV. Gruppe Nachtjagdgeschwader 6 were also involved in these attacks. On April 24, 1945 at around 8:30 p.m., two German Ju 88 night fighters attacked American bivouacs to the left and right of the highway south of Lauf. A contemporary witness who observed the approach reported:

"The plane flew several attacks. The Americans scattered and hid under the vehicles. After the Americans had recovered from their first scare, the plane, which was approaching again, was met with wild defensive fire from hundreds of machine guns. The plane was hit on the third or fourth approach. The plane flew low over Letten and crashed into the boggy forest. The crash site is 150 meters south of today's Waldgasthof-Hotel Letten. The on-board ammunition detonated hours later during the impact fire. The crew died in the crash. One man burned to death in the plane. One was able to get out. The parachute did not open fully, probably due to insufficient altitude, and the man became trapped in the trees and was fatally injured. I don't remember a third man from the crew. The crash site is known to the locals as the "Fliegerloch". The remains of the Ju 88/G-6, with the registration Z 9-10, became a coveted object. In the summer of '45, the first thing the specialists among the scrap material collectors did was to remove the injection pumps and gradually remove all usable items such as engines, electric motors, etc. The Americans also suffered losses in these attacks. The wounded were rescued by US medics. In Himmelgarten, a farmer had to clear out his barn, where a dressing station was set up." (Friedrich Braun archive) (Archiv Friedrich Braun)

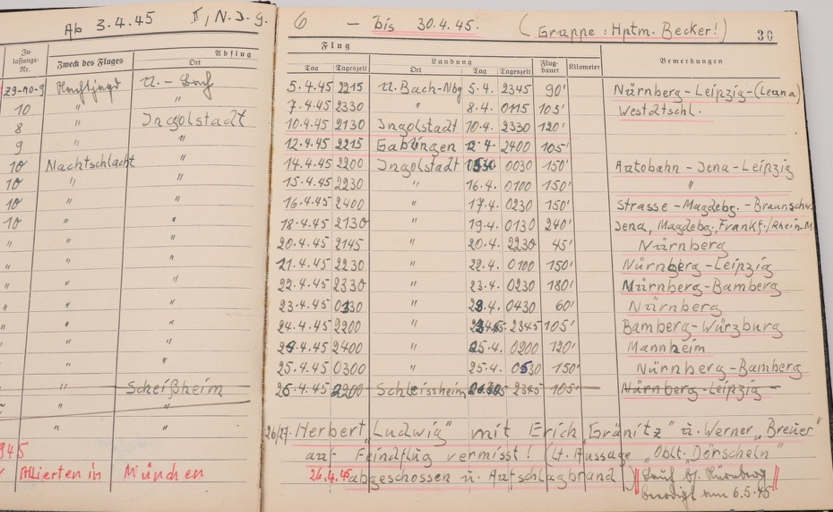

Friedrich Braun began to research the fate of the crew extensively. In the war diary, under April 24, 1945, it says: "1 Ju 88 of IV/NJG 6 with crew Lt. Ludwig missing!" Kock, W. (1996: 287). The pilot of the Ju-88 shot down near Letten was the 25-year-old Leutnant Herbert Ludwig, who also flew the night fighter that was shot down over Fischbach on March 16, 1945 (see p. 113 ff.). As a result of the injuries sustained in the crash, Leutnant Ludwig was unable to fly for several weeks. On April 4, 1945, II/NJG 101, which was based in Unterschlauersbach, was disbanded. The three best crews of II/NJG 101 were Ludwig with 13, Rasper with 11 and Dörscheln with 8 kills. These three crews were transferred to IV/NJG 6 (commander Captain Martin Becker) in Ingolstadt, all other personnel of NJG 101 were transferred to the ground combat units. From Ingolstadt and Schleissheim, the IV/NJG 6 still flew night battle missions on US columns and deployments in April '45. „1 Ju 88 der IV./NJG 6 mit Besatzung Lt. Ludwig vermisst!“ Kock, W. (1996: 287). Flugzeugführer der bei Letten abgeschossenen Ju-88 war der 25-jährige Leutnant Herbert Ludwig, wel cher auch den Nachtjäger flog, der am 16. März 1945 über Fischbach abgeschossen wurde (siehe S. 113 ff.). In Folge der beim Absturz zugezogenen Verwundung konnte Leutnant Ludwig einige Wochen nicht mehr fliegen. Am 4. April 1945 wurde die II./NJG 101, die in Unterschlauersbach lag, aufgelöst. Die drei besten Besatzungen von der II./NJG 101, waren Ludwig mit 13, Rasper mit 11 und Dörscheln mit 8 Abschüssen. Diese drei Besatzungen wurden zur IV./NJG 6 (Kommandeur Hauptmann Martin Becker) nach Ingolstadt versetzt, alles übrige Personal des NJG 101 wurde den Erdkampfeinheiten zugeführt. Von Ingolstadt und Schleißheim aus flog die IV./NJG 6 im April ’45 noch Nachtschlachteinsätze auf US-Kolonnen und Bereitstellungen.

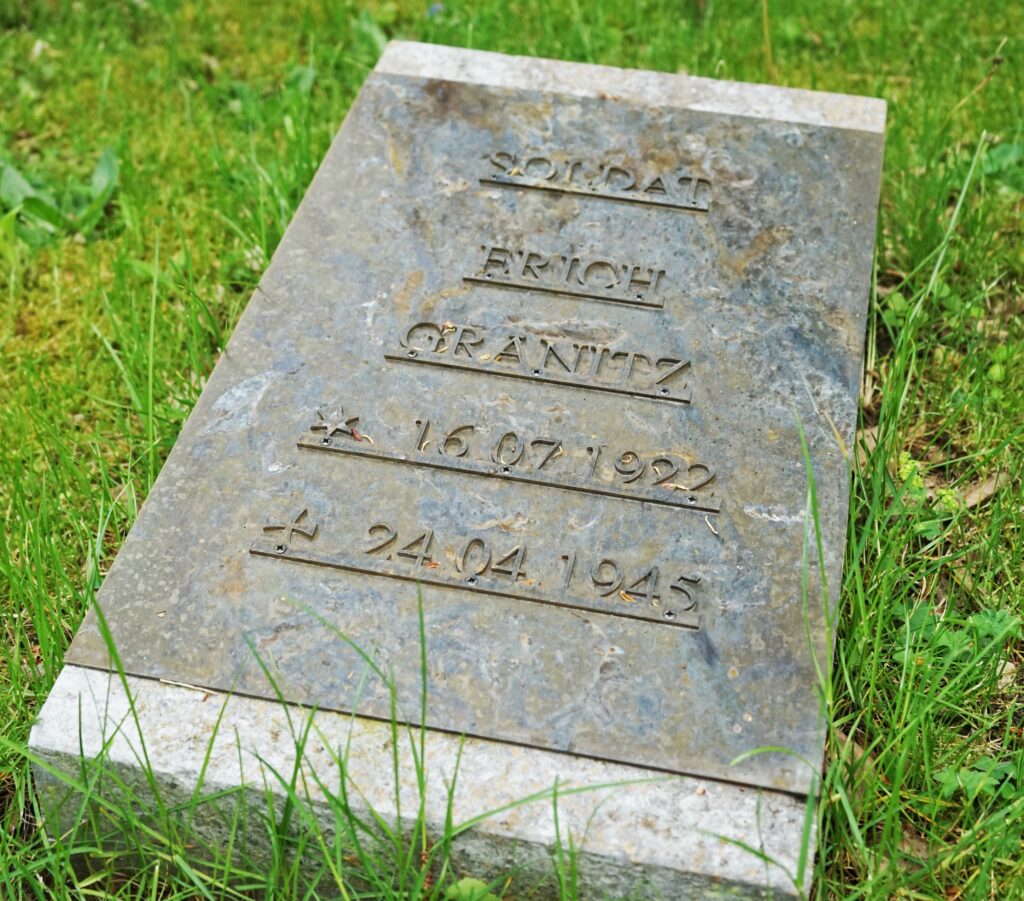

But back to clarifying the events of April 24, 1945 in Letten. The first clues revealed the grave of Uffz. Erich Gränitz from Burkhardtsdorf (Saxony), who was buried in the cemetery in Lauf on May 2, 1945. Erich Gränitz could be assigned without doubt to the Ju 88 in Letten. However, a Ju-88 crew consisted of at least three airmen and the graves of the two other crew members could not be found at first. A search of all the surrounding municipal cemeteries was unsuccessful. Lieutenant Ludwig's final resting place was finally found at the Nagelberg military cemetery near Treuchtlingen. Herbert Ludwig from Neustadt (Upper Silesia) was buried in Schönberg on May 5, 1945 and reburied in Treuchtlingen-Nagelberg in the 1950s. Mrs. Ludwig, the pilot's wife, told Friedrich Braun what happened next. The young woman had given birth to a son in May '45, just at the time when her husband was buried. On July 30, 1945, she was informed in writing by a comrade of her husband that he had not returned from deployment on April 25, 1945. In June 1946, Mrs. Ludwig learned from the Red Cross that her husband had been killed near Letten. Why did Ludwig report for duty again so quickly in the last 158 days of the war after being wounded in the Fischbach crash?

Lieutenant Ludwig's funeral was preceded by days of wrangling. The Protestant pastor of Schönberg refused to bury Herbert Ludwig, who was supposedly a Catholic. Ludwig was finally buried by Father Karch, the Catholic priest of the parish of St. Otto / Lauf, on May 5, 1945 in Schönberg. According to Mrs. Ludwig, her husband was a Protestant. How close life and death were during the war is illustrated by the third man, Sergeant and radio operator Anton Dietrich, who would have been a member of Ludwig's crew. Here is an excerpt from Anton Dietrich's letter to Mrs. Ludwig dated June 30, 1945:

"On April 24, I drove home from Schleissheim (where we were last berthed) in the evening298 to take my laundry away. We weren't supposed to fly that evening because we were preparing to move to Bad Aibling. But then we were ordered to fly a night mission after all. Herbert was assigned to it. In my place, someone else - Uffz. Werner Breuer - had to board the aircraft as an on-board radio operator. Uffz. Erich Gränitz flew along as an on-board mechanic. When I got to the accommodation the next morning, I was told that Herbert hadn't returned. I was devastated. That same night, Oblt. Dörscheln flew night battle in the same room where Herbert had flown. He saw a murderous wall of flak fire in front of him and immediately afterwards an impact fire, which could only have come from Herbert's plane, as no other plane was reported missing."„

(Friedrich Braun archive, letter from on-board radio operator Anton Dietrich to Mrs. Gertrud Ludwig after the war)

According to Mrs. Ludwig's documents, the third unknown airman who had to board the plane as a replacement for Anton Dietrich was Werner Breuer. A typewritten note by Mrs. Ludwig stated that Breuer was buried in Röthenbach a.d. Pegnitz on May 2, 1945. Despite intensive searches in the relevant municipal and church archives, the grave of NCO Werner Breuer has still not been found. It is thanks to Friedrich Braun's research that the events of the crash in Letten can be fully documented. Today, not much remains of the crash over 70 years ago. Only a few insiders are likely to know that the small water-filled depression in the forest south of the Waldgasthof is not of natural origin. Small fragments of the Ju 88 can still be found at the crash site today. However, these are only deformed pieces of sheet metal no more than 10 cm in size. No more meaningful fragments of the plane could be found.

noch Oberfähnrich.

Erich Gränitz.

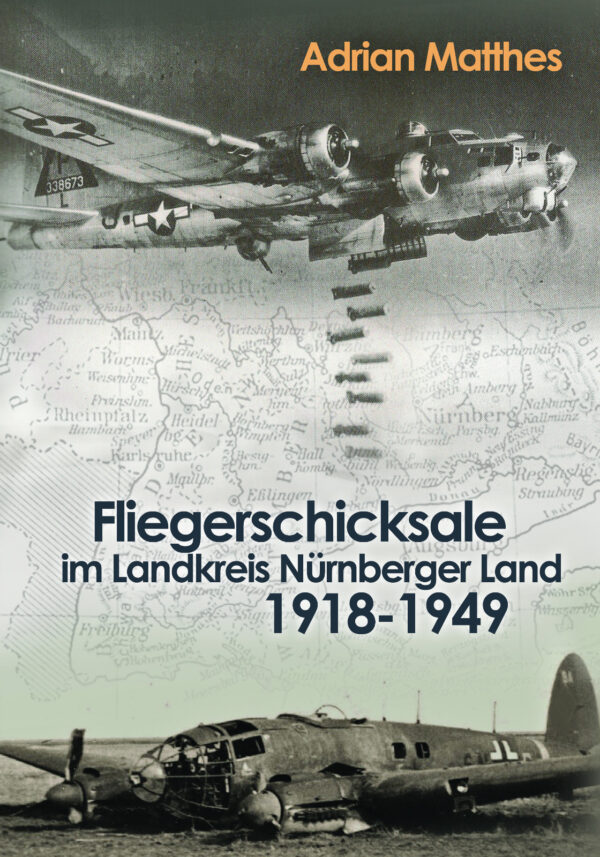

Weitere Recherchen zu Flugzeugabstürzen im Landkreis finden Sie in meinem neuen Buch: Fliegerschicksale im Landkreis Nürnberger Land 1918-1949

Fliegerschicksale im Landkreis Nürnberger Land 1918-1949

Fliegerschicksale im Landkreis Nürnberger Land Adrian Matthes Mit „Fliegerhang“ oder „Fliegerloch“ bezeichnet insbesondere die ältere Bevölkerung bis heute die Aufschlagsstellen abgestürzter Flugzeuge im Gelände – Flurbezeichnungen im Volksmund, hinter denen sich oft Schicksale des Luftkrieges verbergen. Über 40 Flugzeuge fielen zwischen 1918 und 1949 über dem Landkreis Nürnberger Land vom Himmel. In ihnen saßen Flieger…

The tragic last weeks of the night fighter crew Lieutenant Ludwig: Crash over the Nazi Party Rally Grounds

Hello Adrian

this is excellent, I’d like to share some of it – Ludwig’s sortie on 16/17 March -on my blog please http://falkeeins.blogspot.co.uk

There is colour film footage of Ludwig’s Bf 110 also coded 9W+BO discovered at Fritzlar by the Amis

I have translated Rasper’s account of the night of 23/24 April which was published in an old issue of Jaegerblatt

Hello. Sure you can use that… Please link my page…. 🙂

Greetings from Germany

Adrian

Guten Abend Herr Matthes,

in der Nacht vom 29. auf den 30. Mai 1944 schoss Lt. Herbert Ludwig von der 6./NJG 101 eine Vickers Wellington mit der Seriennummer LN318 über Hofstetten-Grünau in Niederösterreich ab. Alle 5 Mann der Besatzung konnten sich mit dem Fallschirm retten und haben den Krieg überlebt. Wir haben nachgeforscht und allerhand Daten zusammengetragen.

Gerne würden wir uns mit Ihnen Austauschen.

Dankeschön.

mit freundlichen Grüßen,

die Gruppe der Heimatforschung Hofstetten-Grünau

Das klingt spannend! ich habe Ihrer Gruppe eine Mail geschrieben und stehe gerne mit Archivmaterial für Ihre Forschungen zur Verfügung.

Hallo Adrian!

thanks for your positive reply. I have just made a blog post and linked to your pages. I know that other English-language readers (and publishers!) are also looking at your work. Gratuliere!